Pentecostalism represents one of the most dynamic and rapidly growing movements in modern Christianity, emerging in the early twentieth century and transforming the religious landscape across the globe. Born from a desire to recapture the spiritual vitality and supernatural manifestations described in the New Testament book of Acts, Pentecostalism emphasizes direct personal experience with God, baptism in the Holy Spirit, and the continuation of spiritual gifts such as speaking in tongues, prophecy, and divine healing. What began as a small revival meeting in Los Angeles has grown into a worldwide phenomenon encompassing hundreds of millions of believers across every continent.

The Azusa Street Revival: The Birthplace of Modern Pentecostalism

The story of modern Pentecostalism cannot be told without examining the Azusa Street Revival, a series of meetings that began in April 1906 in a humble building at 312 Azusa Street in Los Angeles, California. This former African Methodist Episcopal church, which had been converted into a warehouse and stable, became the unlikely epicenter of a spiritual awakening that would send shock waves throughout the Christian world.

The revival was led by William J. Seymour, an African American preacher and the son of former slaves. Seymour had been influenced by the teachings of Charles Parham, who had established a connection between baptism in the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues at his Bethel Bible School in Topeka, Kansas, in 1901. However, it was at Azusa Street that these beliefs found their most explosive expression and widest dissemination.

The meetings at Azusa Street were marked by several revolutionary characteristics that would define Pentecostalism. Services were spontaneous and often lasted for hours, with no set program or liturgy. Participants reported dramatic experiences of spiritual ecstasy, including speaking in unknown languages, prophesying, experiencing visions, and receiving divine healing. The worship was emotionally expressive, featuring shouting, weeping, dancing, and physical manifestations that shocked observers accustomed to more reserved religious services.

Perhaps most remarkably for early twentieth-century America, the Azusa Street Revival broke through racial and social barriers. Black and white worshipers gathered together in an era of rigid segregation, and women were permitted to preach and lead services, challenging prevailing gender norms. This interracial and egalitarian character, though it would not fully persist in all branches of Pentecostalism, was a distinguishing feature of the revival’s early years.

News of the revival spread rapidly through word of mouth and through “The Apostolic Faith,” a newsletter published by the Azusa Street Mission. Pilgrims traveled from across the United States and around the world to witness and participate in the meetings. Many of these visitors took the Pentecostal message back to their home communities, planting seeds that would grow into churches, denominations, and movements. The revival continued with varying intensity until roughly 1909, but its influence extended far beyond those three years, establishing patterns of worship and belief that continue to characterize Pentecostalism today.

Doctrinal Foundations and Distinctive Beliefs

While Pentecostalism shares much common ground with evangelical Christianity, including beliefs in biblical authority, salvation through faith in Jesus Christ, and the importance of personal conversion, it possesses distinctive theological emphases that set it apart. Central to Pentecostal belief is the doctrine of baptism in the Holy Spirit as a definite experience subsequent to conversion, accompanied by speaking in tongues as the initial physical evidence of this baptism.

A significant stream within Pentecostalism developed theological perspectives that distinguished it from other evangelical groups on fundamental questions of the nature of God and the requirements for salvation. This perspective emphasizes the absolute oneness and unity of God, rejecting multi-personal conceptions of the divine nature. Adherents of this view believe that God is one in numerical value and that Jesus Christ is the complete embodiment of all divine fullness, not merely one person among others in a godhead.

This theological position is grounded in specific biblical passages, particularly from the Gospel of John and the writings of Paul. Passages such as “I and my Father are one” and “he that hath seen me hath seen the Father” are understood to teach that Jesus is not separate from the Father but is himself the Father manifested in flesh. The phrase “in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” from Matthew 28:19 is understood to refer to a singular name, which is identified as Jesus, based on the apostolic practice recorded in the book of Acts.

This perspective leads to distinctive practices in water baptism. Rather than using a formulaic invocation of three titles, baptism is performed in the name of Jesus Christ, following the pattern found in Acts 2:38, Acts 8:16, Acts 10:48, and Acts 19:5. This is not viewed as a mere technicality but as obedience to apostolic teaching and practice. Water baptism is considered an essential step in salvation, not as a work that earns salvation but as an act of faith and obedience through which one receives remission of sins.

The full plan of salvation, according to this perspective, involves three essential elements: repentance from sin, water baptism in the name of Jesus Christ for the remission of sins, and baptism in the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in other tongues. These three experiences correspond to the complete new birth described in John 3:5, “Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God.” The emphasis on these specific experiences and formulae creates a distinctive soteriological framework within the broader Pentecostal movement.

Holiness of life is strongly emphasized, with adherents expected to live in separation from worldly practices and to pursue sanctification. This often includes specific standards of conduct regarding dress, entertainment, and lifestyle. Women are typically encouraged to wear modest clothing, avoid cutting their hair (based on interpretations of 1 Corinthians 11), and refrain from wearing makeup or jewelry. Television, movies, and other forms of secular entertainment are often discouraged or prohibited. These standards are not viewed as legalistic requirements for earning salvation but as outward expressions of inner spiritual transformation and commitment to biblical principles.

The Emergence and Development of the United Pentecostal Church International

The organizational history of this stream of Pentecostalism reflects the theological distinctives that set it apart from other branches of the movement. In the years following the Azusa Street Revival, various Pentecostal groups formed around different doctrinal emphases and organizational structures. By the mid-1910s, a significant doctrinal controversy had emerged within Pentecostalism concerning the nature of God and the proper formula for water baptism.

The issue came to a head at a camp meeting in 1913 near Los Angeles, where R.E. McAlister preached a sermon on baptism in which he noted that the apostles in the book of Acts had baptized in the name of Jesus Christ rather than using the formula “Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.” This observation sparked intensive biblical study among those present, particularly Frank J. Ewart and Glenn A. Cook, who began to develop a comprehensive theological framework around the oneness of God and the singular name of Jesus.

In 1914, a number of Pentecostal ministers and churches, seeking greater cooperation and organization, formed the General Council of the Assemblies of God in Hot Springs, Arkansas. However, as the new doctrine concerning God’s nature and baptismal formula spread, it created significant controversy within this young organization. By 1916, the Assemblies of God adopted a “Statement of Fundamental Truths” that explicitly affirmed a view of God as three distinct persons, leading to a definitive split. Ministers who held to the oneness position were forced to leave or voluntarily withdrew from the Assemblies of God.

Those who departed formed their own organizations and networks. In 1917, the General Assembly of Apostolic Assemblies was formed, primarily consisting of former Assemblies of God ministers who had embraced the Jesus’ name baptism and non-trinitarian theology. Around the same time, another organization called the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World (PAW) was growing, which also held to these doctrinal positions. The PAW was notable for its interracial character, including both black and white ministers and members.

However, racial tensions and social pressures of the era created challenges for this interracial fellowship. In 1924, most of the white ministers withdrew from the PAW to form the Pentecostal Ministerial Alliance. This organization went through several name changes and reorganizations over the following years, reflecting the fluid and sometimes contentious nature of early Pentecostal organizational development. In 1932, it became the Pentecostal Church, Incorporated, and in 1937, it merged with another group to form the Pentecostal Church of Jesus Christ.

Meanwhile, another organization had emerged in 1932 called the Emmanuel’s Church in Jesus Christ. This group had formed from ministers who had also separated from other Pentecostal bodies over doctrinal issues. For several years, these two organizations—the Pentecostal Church of Jesus Christ and the Emmanuel’s Church in Jesus Christ—existed separately, though they shared virtually identical beliefs and practices.

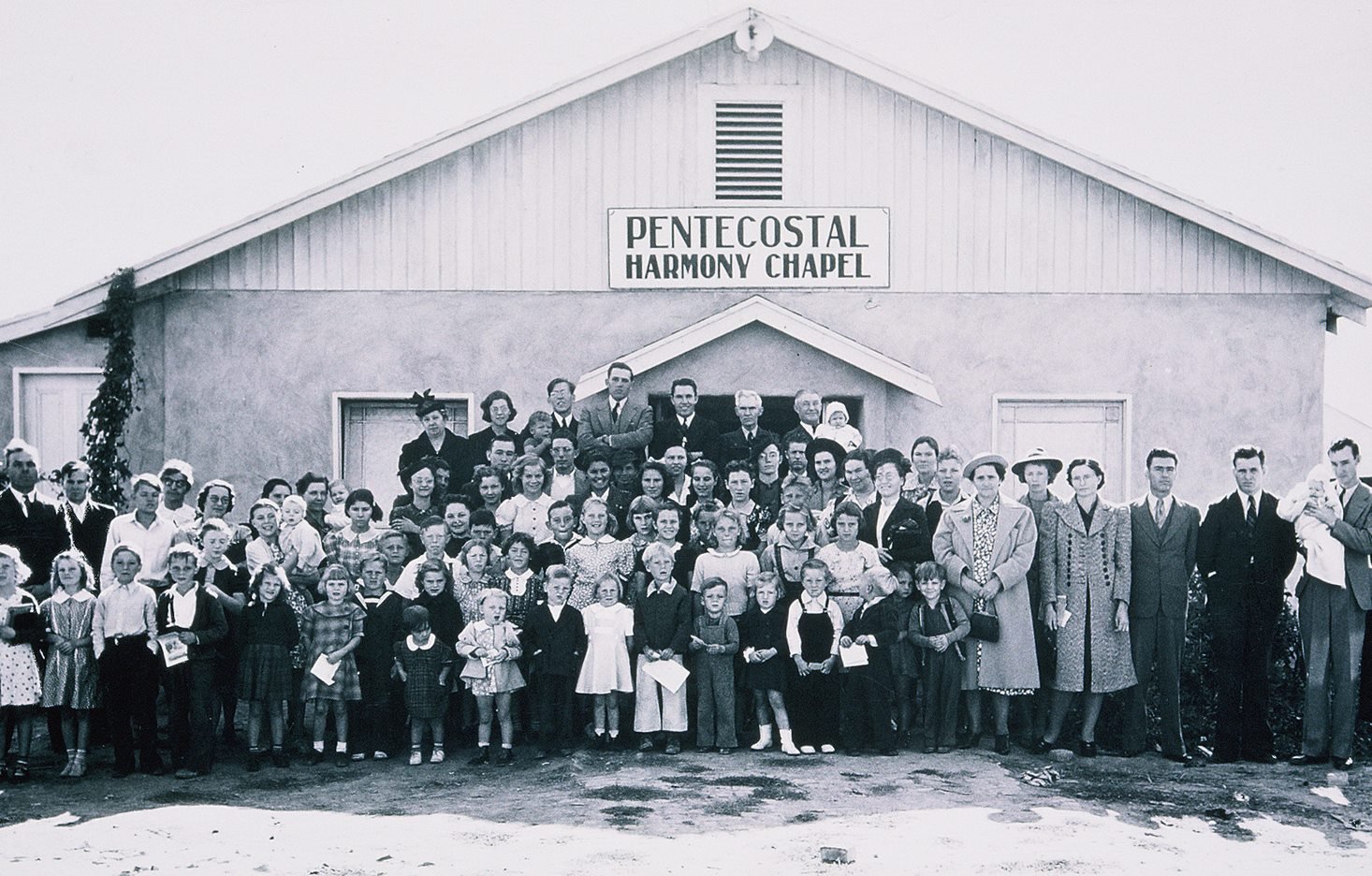

Recognizing the inefficiency and weakness of maintaining separate organizations with the same message and mission, leaders from both groups began discussions about merging. These discussions bore fruit in 1945 when representatives gathered in St. Louis, Missouri, for a unification conference. On September 13, 1945, the two organizations officially merged to form the United Pentecostal Church (UPC). This merger brought together approximately 521 ministers and represented a significant consolidation of churches and believers who held to the distinctive doctrines of Jesus’ name baptism and the oneness of God.

The new organization adopted a cooperative structure with both national and district-level governance. A General Superintendent and other general officers were elected to provide leadership, while district organizations maintained regional oversight and fellowship. The church adopted a Statement of Fundamental Doctrine that clearly articulated its beliefs concerning the nature of God, the plan of salvation, and standards of holiness.

In 1965, the organization added “International” to its name, becoming the United Pentecostal Church International (UPCI), reflecting its growing missionary work and global presence. What had begun as a predominantly North American organization was expanding rapidly into other nations through aggressive missionary efforts and indigenous church planting.

Growth, Expansion, and Global Impact

From its formation in 1945, the United Pentecostal Church International experienced steady and then explosive growth. The post-World War II era brought new opportunities for evangelism and church planting, both domestically and internationally. Returning soldiers who had been converted or called to ministry during the war provided leadership and energy for expansion. The development of new communication technologies, including radio and eventually television, provided additional platforms for spreading the Pentecostal message.

Missionary work became a central focus of the organization. The UPCI established a missions division that recruited, trained, and supported missionaries to serve in nations around the world. Unlike some missionary approaches that focused primarily on Western expatriates leading foreign works, the UPCI emphasized developing indigenous leadership, translating materials into local languages, and planting self-supporting national churches. This strategy proved highly effective, and the organization saw rapid growth in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and other regions.

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, the UPCI had become a truly global organization with a presence in more than 200 countries and territories. While exact membership numbers are difficult to determine due to varying record-keeping practices in different nations, the organization has reported having thousands of churches and millions of adherents worldwide. The international constituency has actually surpassed the North American membership, reflecting broader trends in global Christianity toward growth in the Global South.

The organization established educational institutions to train ministers and church leaders. These included both formal Bible colleges and certificate programs designed to provide theological education while maintaining strong emphasis on spiritual experience and practical ministry skills. The curriculum at these institutions reflects the distinctive doctrines of the movement, ensuring that graduates are thoroughly grounded in the theological positions that define the organization.

Publishing became another significant ministry arm. The UPCI operates a publishing house that produces Sunday school curricula, books, tracts, and other materials that articulate and defend its doctrinal positions while providing practical resources for church ministry. These materials are distributed not only through official channels but also by independent ministers and churches that share the same beliefs, extending the influence beyond formal organizational boundaries.

Youth and children’s ministries received increasing emphasis as the organization matured. The development of youth conventions, camps, and specialized programs reflected recognition that retaining the next generation required intentional investment. These programs combined the traditional emphases on spiritual experience and holiness with approaches designed to engage young people in contemporary cultural contexts.

Challenges, Controversies, and Continuing Debates

Like all religious movements, this stream of Pentecostalism has faced various challenges and controversies throughout its history. The distinctive doctrinal positions, particularly regarding the nature of God and the requirements for salvation, have made adherents targets of criticism from other Christian groups. Many evangelical and mainstream Christian organizations have classified these beliefs as heretical or cultic, leading to social and religious marginalization in some contexts.

The emphasis on strict holiness standards has created ongoing debates within the movement about the relationship between grace and works, between essential doctrines and cultural applications, and between biblical principles and their practical implementation. Questions about whether specific standards (such as those concerning dress and entertainment) are timeless biblical mandates or cultural applications subject to change have generated discussion and sometimes division.

Gender roles represent another area of ongoing conversation. While women have been permitted and even encouraged to participate in various forms of ministry, including evangelism, teaching, and missionary work, there have been restrictions on women serving in certain leadership capacities, particularly as senior pastors of local churches. This reflects interpretations of biblical passages addressing gender and ministry, but it has also sparked debate as cultural understandings of gender roles have evolved.

The organization has also grappled with questions about how to engage with broader culture and society. Early Pentecostalism was often characterized by strong separation from “the world,” with prohibitions on many forms of entertainment, recreation, and social engagement. As subsequent generations have grown up in different cultural contexts and as society itself has changed dramatically, questions arise about which separations are essential to biblical holiness and which may be outdated cultural expressions.

Internal governance and authority structures have occasionally been sources of tension. Balancing local church autonomy with organizational unity, managing property and assets, handling ministerial credentials and discipline, and responding to theological or ethical controversies have required ongoing attention and sometimes difficult decisions. The cooperative structure of the organization attempts to maintain fellowship and unity while respecting the independence of local congregations, but this balance is not always easy to achieve.

Despite these challenges, the movement has demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability. The fundamental emphasis on spiritual experience—particularly the baptism in the Holy Spirit with speaking in tongues—provides a unifying center that transcends many secondary disputes. The conviction that the message and mission are biblically mandated creates strong motivation for evangelism and church planting even in the face of opposition or marginalization.

Contemporary Expression and Future Directions

In the early twenty-first century, this branch of Pentecostalism continues to evolve while maintaining its core distinctive doctrines. Contemporary worship styles incorporating modern music and technology coexist with traditional emphases on spiritual gifts and manifestations. Churches range from small rural congregations meeting in modest buildings to large urban megachurches with sophisticated media productions and multiple services.

The movement has produced numerous Bible schools, conferences, and media ministries that spread its distinctive message. While maintaining its theological distinctives, there has been some softening of certain cultural positions in some congregations, with greater diversity in application of holiness standards, though this varies considerably by region and local church culture.

The global nature of the movement has introduced new dynamics. Churches in Asia, Africa, and Latin America often face different cultural contexts and challenges than those in North America or Europe, requiring contextual application of biblical principles. Indigenous leaders in various nations have developed their own expressions of Pentecostal worship and ministry while maintaining the core doctrinal distinctives.

Social media and internet technologies have created new opportunities for spreading the message but also new challenges for maintaining organizational identity and doctrinal consistency. Online preaching, digital evangelism, and virtual church services expanded dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic and continue to be significant ministry platforms.

The movement continues to emphasize evangelism and church planting as primary activities. The conviction that salvation comes through specific experiences—repentance, baptism in Jesus’ name, and baptism in the Holy Spirit—creates urgency for sharing this message with those outside the faith. Missionary work remains a central organizational priority, with continuing expansion in unreached regions and people groups.

The Future of Pentecostalism

Pentecostalism, emerging from the fires of the Azusa Street Revival, represents a powerful force in contemporary Christianity. This particular expression of Pentecostalism, with its distinctive teachings about the nature of God and the plan of salvation, has grown from controversial beginnings in the early twentieth century to become a global movement with millions of adherents.

The formation and development of the United Pentecostal Church International represents a significant chapter in this story, demonstrating how doctrinal distinctives can provide the basis for organizational identity and mission. From the merger of two small organizations in 1945 to its current status as an international movement, the UPCI exemplifies both the vitality and the complexity of modern Pentecostalism.

The emphasis on direct spiritual experience, the practice of spiritual gifts, and the insistence on apostolic patterns of faith and practice continue to attract converts and inspire devotion. The strict standards of holiness, while challenging in contemporary culture, provide clear boundaries and identity markers for believers seeking to live distinctively Christian lives in a secular age.

As with all religious movements, questions remain about how this stream of Pentecostalism will navigate the challenges of cultural change, generational transition, and global diversity while maintaining its distinctive identity. The theological convictions that define the movement—particularly regarding the oneness of God, baptism in Jesus’ name, and the necessity of baptism in the Holy Spirit—provide strong foundations, but their application and expression in diverse contexts will require ongoing wisdom and discernment.

What is clear is that this form of Pentecostalism will continue to be a significant presence in global Christianity, offering a distinctive message about the nature of God, the plan of salvation, and the possibility of direct, transformative encounter with divine power. Whether one accepts or rejects its particular theological framework, its impact on the religious landscape of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is undeniable, and its influence shows no signs of diminishing in the years ahead.